Building Management Statements 101

We first wrote about building management statements (‘BMS’) nearly three years ago here.

That newsletter predicted that we were going to get more and more disputes about these documents, which has proved to be the case. If only we could pick the lotto numbers for Saturday night, we’d be in clover. Until that day happens, we are stuck grinding away in a legal practice.

In hindsight, in the first article we wrote about BMS tipped straight into the detail. What would have been better is a bit more of an explanatory guide as to what a BMS is, how they work, what regulates them and what we see as the issues for bodies corporates who are parties to them.

What is a Building Management Statement?

In many long established cities (i.e. Paris, New York), mixed-use buildings are the norm. Retail and commercial are on the ground floor with residential units sitting above them. Australia is starting to catch up and mixed-use developments are becoming more frequent in urban areas.

There are a few ways to set up a mixed-use development, including:

- A single scheme – a body corporate will be constituted by the owners of all lots, irrespective of their use. A common issue that arises: does that mean that people in the commercial lots can use the swimming pool?

- A layered scheme – there will be retail, commercial and residential bodies corporate in the one building that are all members in a principal body corporate. Figuring out what the principal body corporate is responsible for can be a nightmare…

- Separate lots for different parts of the building, which are subject to a BMS.

A BMS can only exist where there are at least two lots, one of which must be a volumetric format lot. A volumetric format lot, in its simplest terms, is a lot created by the subdivision of air space.

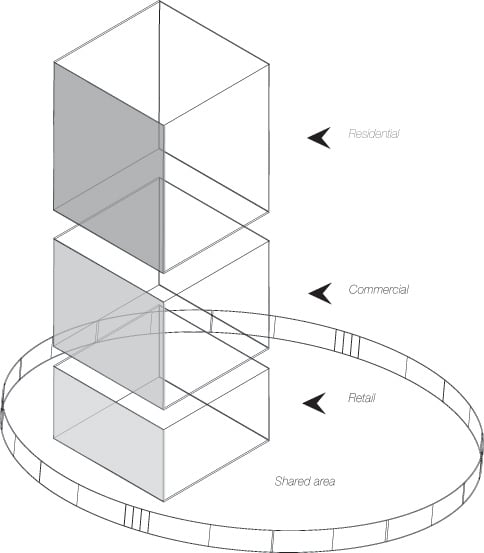

What happens in many newer style tower developments is that components of a building are put together (for example, retail, commercial and residential) and those individual components are created in volumetric lots. Each of those volumetric lots can then be subdivided again (or kept in one lot), which is what happens in the majority of new mixed-use tower developments.

The BMS then regulates how each of those lots relates.

See below image for how this would look:

The original owner of each of those volumetric lots signs that lot up to the BMS and then each later subdivided lot inside the original lot becomes subject to the BMS.

So in the above example, the retail lot could be kept in one line. The office lot could be strata titled into separate commercial offices and the residential lot could then be strata titled into separate residential lots. There would still only be three parties to the BMS but two of them would now consist of the bodies corporate of the residential and commercial lots.

What does a BMS regulate?

It regulates the shared areas between the lots and joint obligations. These include things like insurance, management, lifts, car park egress and ingress, walkways and foyers and so on. Basically, anything that more than one of the parties to a BMS will use.

Nearly all BMS’ set out the proportion of costs that each lot will bear with respect to the shared areas and also the BMS management structure and voting rights.

How binding is a BMS?

In a word– very.

The BMS is a contract. Like any contract it can only be changed with the consent of the parties to it. Obtaining the consent of the Body Corporate to a change of BMS is beyond the scope of this article but it is not without its difficulties.

Can you review a BMS?

Not unless the BMS itself allows it. A BMS is not subject to statutory review (unlike (probably) lot entitlements shortly). Therefore, the cost proportions for shared facilities set out in the BMS are going to be that for the life of the building which it governs.

Where do you ventilate disputes?

As a BMS is not regulated by the Body Corporate and Community Management Act 1997. Disputes in relation to them are not resolved in the Commissioners Office.

This means that litigating a BMS issue is through a dispute resolution mechanism set out in the BMS or before the normal Courts of Queensland with all of the attendant processes, time delays and costs.

Say what you like about the Commissioner’s Office, but it is a low cost forum which is relatively effective in getting disputes decided quickly.

So where are there headaches?

There are a few common themes we are seeing:

Agreement on cost proportions

BMS’ do not always set out an appropriate method of calculation of the apportionment of shared costs. They can be left as a base level assumption with the ability for them to be varied. The question then becomes on what basis costs are shared? In one recent matter we were involved in, a quantity surveyor went to the extent of counting the electrical outlets in the shared areas that each lot was likely to use and we then documented the apportionment of electricity on that basis. Other expenses were then shared based on different proportions which depended on use.

Financial management

We continue to come across situations where the BMS accounts are run out of the residential body corporate leaving potential contingent liabilities. What happens if there is a dispute about the amounts spent from the other parties to the BMS?

This was covered in our prior article and it remains a source of ongoing contention.

From our end, it is only a matter of time before a residential body corporate gets caught to the tune of tens of thousands of dollars because it cannot recover what it has spent. Each body corporate involved in a BMS should set up an appropriate BMS management group (together with the incumbent cost and management structure) to properly administer the affairs of the BMS. While there is an ongoing cost, it is a very cheap form of insurance if a dispute arises.

The best practice for us seems to be that buildings that have a BMS should create separate accounts, books and records. This might even be to the extent of having a separate strata manager or facilities manager administer them. That is the case even if the residential body corporate and the BMS are managed by the same strata management company. Different people can be the manager under the same company. That way, there is a clear line of demarcation internally that prevents the potential (inevitable) conflicts that come from wearing two hats in one engagement.

Inequitable cost sharing

This one is harder to solve because the BMS is a contract. We have seen two instances so far where the cost sharing mechanism appears clearly inequitable – and you can guess who benefits from that (and it is not our body corporate clients). On a stand alone annual basis the additional costs might not seem too bad – but extrapolate it for the life of the building and no matter how small it might be, it adds up to a decent figure.

As always, if you need help, we’re only an email away.